This is the first of a series of historical articles about the St Anne’s Valleys: that is, St Anne’s Wood and its sister wood, Nightingale Valley. This article covers the high medieval period, from AD 1000 to 1300.

Medieval Land Tenure in the St Anne’s Valleys

Prior to the 10th century, Anglo-Saxon England was made up of seven large kingdoms: Kent, Sussex, Wessex, East Anglia, Essex, Mercia and Northumbria. Brislington was in the Kingdom of Wessex. In 927, Æthelstan the Glorious, originally the king of Wessex and Mercia, became the first Anglo-Saxon king to have effective rule over the whole of England.

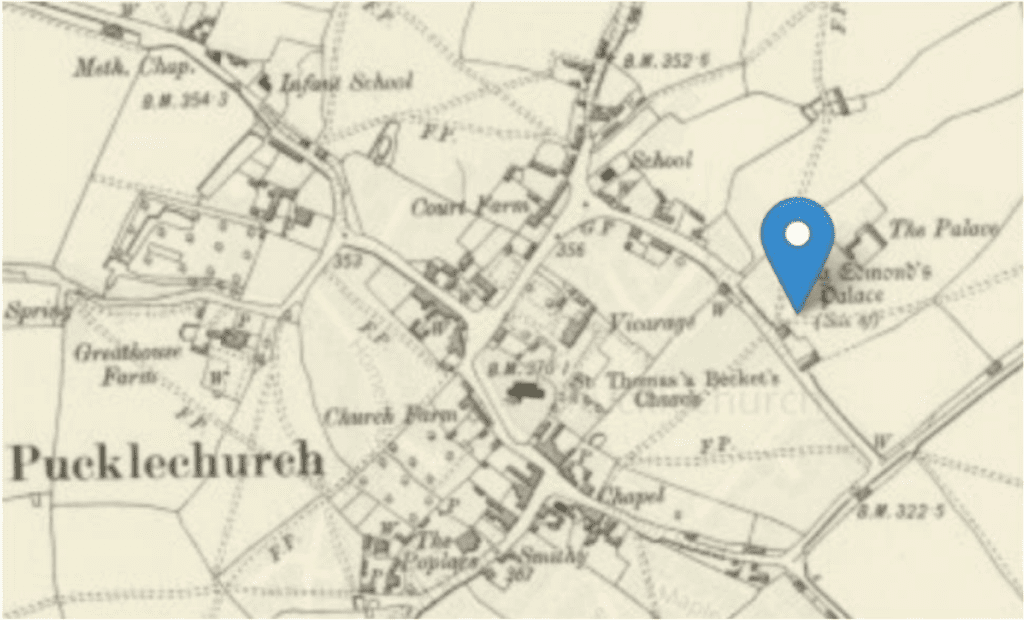

One of his royal palaces was located in Pucklechurch (Pulcrecerce) in Wessex. In 946, Æthelstan’s half-brother, King Edmund I, was murdered at the palace by a thief he had previously outlawed.

The St Anne’s Valleys – St Anne’s Wood and Nightingale Valley – then in Somersetshire, are remnants of woodland that was once hunted from Pucklechurch palace. They were located in Fillwood Forest and were within the bounds of Kingswood Forest, the bulk of which was to the north of the Avon1. Fillwood Forest was also known as ‘Gallows Wood’, so named because of the presence of a gibbet in Broomhill2. The gibbet was last used in the late 18th century3. Fillwood Forest was attached to, or otherwise placed (by the king) under the authorities of Kingswood Forest, ‘the rangership, or wardenship, being always appointed to the officers of the latter’4.

At the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066, Brislington was part of Keynsham (Cainesham) hundred5. The Doomsday Book of 1086 reveals that the Keynsham hundred consisted of fifty hides6, forty-nine of which were owned by Edith (Eadgyth) of Wessex. Edith was the widow of Edward the Confessor, the penultimate Anglo-Saxon king of England, and sister to Harold II, the last Anglo-Saxon king who was killed in the Battle of Hastings.

According to the Geld Inquest of 1084, the remaining hide was owned by the Priest of Keynsham. The evidence suggests that a substantial Anglo-Saxon church stood in Keynsham in the pre-Conquest period7.

Following his coronation on Christmas Day 1066, William Duke of Normandy, now William I, dispossessed the Anglo-Saxon nobles. William I made the unprecedented claim that every acre of England belonged to him by right of conquest8. He introduced feudalism, a strict hierarchical system, based on land being exchanged for military service, and allegiance to the king under oath. In so doing, he created an aristocracy of Norman barons who became tenants-in-chief of vast swathes of land.

Edith was the exception. William I, sent envoys to Winchester, the then capital of England, to request tribute from her. Edith complied and thereby retained her dower estates9. She was the sole figure among the Anglo-Saxon royalty to prosper during the reign of William I. The Doomsday Book reveals that she was the richest woman in England, and the fourth wealthiest individual. Edith retained Keynsham hundred as an overlord until her death in 1075, when it became crown property.

A pious man, William I allowed twenty-five percent of land in England to remain under the control of the Roman Catholic Church, replacing Anglo-Saxon bishops and abbots with Normans. As a result, Keynsham hundred retained its church land. Since all land in the kingdom of England belonged to William I, the Church merely held the land.

Kingswood Forest, including Fillwood, became the hunting-preserve of William I. It was governed by forest law10, which dictated that hunting animals, felling trees and cutting underwood were prohibited to all but the king and his hunting party11. There were sixty- eight royal forests in the time of William I12 Kingswood Forest was small in comparison to, say, the New Forest.

The wardship of Kingswood Forest was held by Bishop Geoffrey, the first constable of Bristol Castle and chief warden of the forest13. Bishop Geoffrey employed verderers (judicial officers), who were responsible for protecting and preserving the venison and vert for the King’s pleasure14. By all accounts, William I loved the wild deer as though he were their father; and made a law, ‘that whosoever shall slay hart or hind, man shall be made blind’15.

In 1087, William I died while campaigning in France and his son, also named William, ascended to the throne. William II (William Rufus) granted the honour of Gloucestershire to his kinsman, Robert Fitzhamon, a battle-worn military commander16. Fitzhamon’s substantial feudal barony was spread over several counties. It included Brislington, which became a manor in its own right in 1088.

As tenant-in-chief, Fitzhamon provided knights for the king’s feudal army, one for each of the manors he held. This equated to two-hundred and-forty-seven knight fees17. These fully armed and equipped knights pledged military service to the crown for forty days each year.

Fitzhamon died of wounds received in battle in 1107, leaving four young daughters, the eldest of whom, Mabile, inherited his baronial estate. In 1119, Mabile married Robert FitzRobert, the illegitimate son of Henry I18. Robert was created the first Earl of Gloucester and the honour of Gloucestershire, including the manor of Brislington, passed to him.

The second Earl of Gloucestershire, William FitzRobert, has some significance to this story. In 1172, Earl William founded an Augustinian abbey on the site of the Anglo-Saxon church in Keynsham, at the behest of his only son and heir who died in 116619. The abbot of Keynsham Abbey became the first lord of Keynsham. Crucially, Earl William endowed land in his honour to the abbey. This included three-hundred acres of woodland in Fillwood Forest and a fishpond in Nightingale Valley20. The St Anne’s Valleys thus became church land, albeit king’s land that was held by the church.

The la Warres

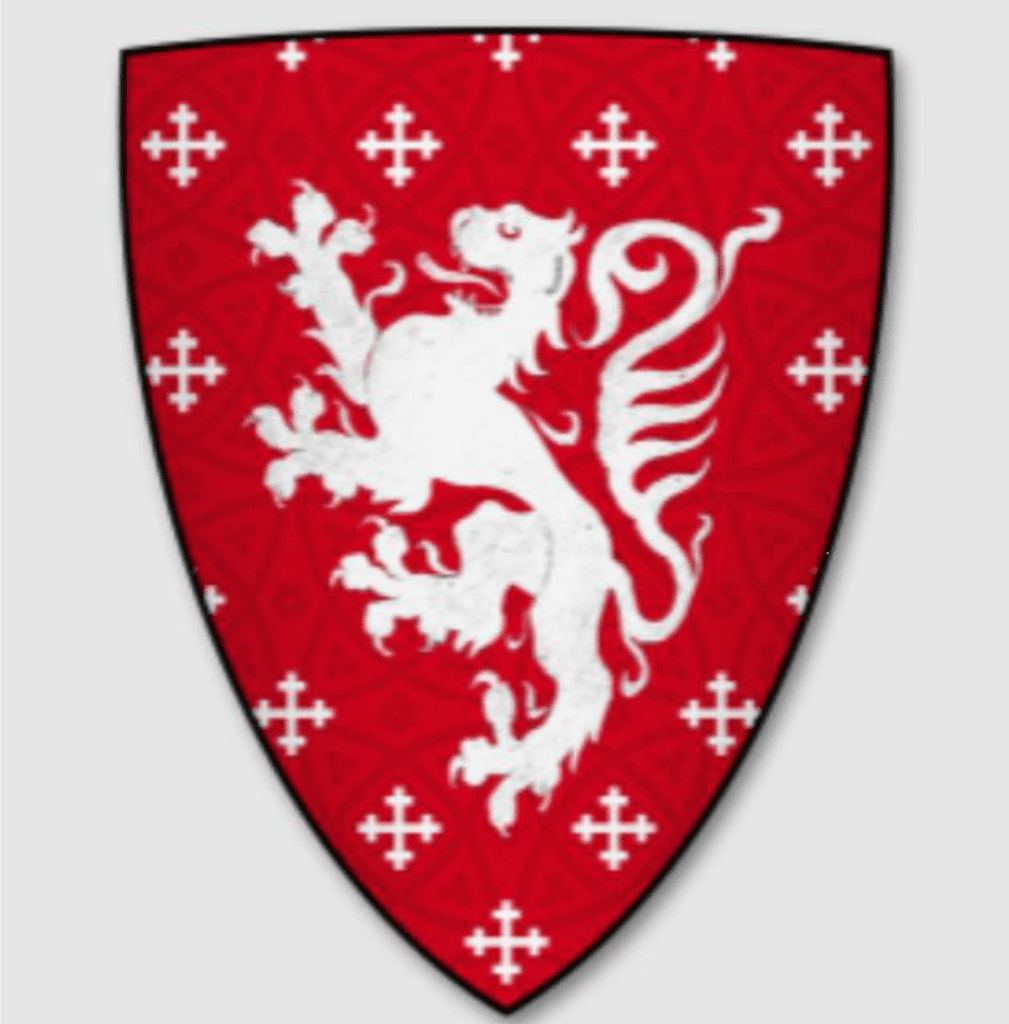

In 1207, the fourth Earl of Gloucester, King John (who had inherited the earldom after marrying Earl William’s daughter, Isabella), granted half the manor of Brislington to a knight named Sir John la Warre (1156-1212)21. The grant excluded the St Anne’s Valleys in Fillwood Forest, which King John kept for himself22; irrespective of the fact that the land had already been granted to the abbot of Keynsham. As the first lord of Brislington, John la Warre performed knight-service for half a knight’s fee: that is, twenty days a year. He served as a naval commander and warrior in the Normandy campaign, commanding a flotilla of British ships23.

John and his family lived in a fortified manor house in Brislington, complete with a moat. Parts of the manor house dated back to Anglo-Saxon times24. Later known as Manor House Farm, it was demolished in 1933 to make way for the Imperial Sports Ground25. John also held the manor of Wickwar in South Gloucestershire, granted to him in 1185 by the then Prince John, for his bravery in battle26. It is likely he spent time at both residences, when feudal obligations permitted. John died in 1212 and was buried at St Mary’s Church in Saltford.

It was John’s great-grandson, Roger la Warre (1255-1320), ‘a wise and valiant knight’27, who put the St Anne’s Valleys on the medieval map. In 1276, Roger founded the Chapel of St-Anne-in-the-Wood, a daughter chapel of Keynsham Abbey, which rose to great prominence as a pilgrim site.

To place the foundation of St Anne’s Chapel within its historical context, the la Warres hadbeen embroiled in a long-running dispute with the respective abbots of Keynsham Abbey. Land tenure in the St Anne’s Valleys was a complicated matter, further complicated by the fact that Fillwood Forest ultimately belonged to the king. The conflict was largely caused by a lack of strong delineating boundaries between the manner of Brislington and that of Keynsham. The dispute came to a head in 1275, when the abbot of Keynsham took the la Wares to court28. The abbot accused the la Warres of dispossessing him of land in the St Annes Valleys. He complained that he had been barred entry to his:

three-hundred acres of wood where [he] used to have common rights with all hisbeasts at all times, excepting pigs in the forbidden month29.

The court ruled in the abbot’s favour, deciding that he had been unjustly disposed of his land30. The following year, Roger founded the chapel of St-Anne-in-the-Wood, seemingly to appease the abbot of Keynsham. Roger la Warre was raised to the peerage in 1298 by Edward I31.

Conclusion

In the high medieval period, the St Anne’s Valleys were held by the la Warre family and the Priest of Keynsham. The overlord was the respective king who used the land as a royal hunting preserve. King John (r. 1199–12.16) intermittently led hunting parties in the St Anne’s Valleys, crossing the Avon on horseback at Conham, at low tide. to access the Fillwood section of Kingswood Forest. His son Henry III (r. 1216-1272) did likewise, as did his grandson, Edward I (r. 1272-1307). The next article will discuss the chapel of St-Anne-in-the-Woods.

Written by Jackie Friel, a volunteer with Friends of Brislington Brook and local historian: https://www.facebook.com/tenamazingtrees/

1 Baine (1891): 2.

2 Moore (1982): 49.

3 Winchester (1986) 87.

4 Braine (1891): 37.

5 From the seventh century onwards, English counties were divided for legal and administrative purposes into areas called ‘hundreds’. Hundreds were formed out of larger equally coherent districts, great blocks of fifty to a hundred square miles. The northern boundary of the Keynsham Hundred was the river Avon.

6 A ‘hide’ was a unit of land sufficient to support an extended family. It was the standard unit of assessment used for tax purposes.

7 Prosser (1995): 110. Bishop Heumund, a warrior-bishop who was drafted by King Æthelred and killed by the sword in battle, was buried in Keynsham in 871.

8 Tombs (2014): 44

9 A ‘dower’ was provision made by a husband to a wife for her support should she become widowed.

10 At its height in the thirteenth century, an estimated one fourth of the land area of England came under the special jurisdiction of forest law. See Young (1979).

11 Jones (1899): 15.

12 Braine (1891): 17.

13 Briane (1891): 18.

14 Venison referred to red deer, fallow deer, roe deer and the wild pig; vert to the woodland and habitat in which they lived.

15 Briane (1891): 18.

16 An ‘Honour’

17 Douglas and Greenaway (1959): 895–944. A ‘knight’s fee’ was a measure of land deemed sufficient to support a knight.

18 William II (Rufus) died in a ‘hunting accident’ in 1100. His younger brother Henry (later Henry I) was implicated.

19 Prosser (1995).

20 Page (1911).

21 Lindegaard (1993). Knights invariably came from wealthy, aspirational families. At the age of seven, a would-be knight was sent to the local manor house to train as a page. On reaching his teens, he trained as a squire, learning to fight with lance and sword. He accompanied his lord to war, holding the reigns of his horse when fighting was on foot. After seven years’ service as a squire, he underwent a lengthy ritual of homage and dedication before entering the knighthood. See: Yapp (1993).

22 Charters, Number 237 (), :172.

23 Ware (2022).

24 Brislington Conservation and History Society (1984).

25 The la Warre’s manor house stood at the corner of Sturminster Road and West Town Lane.

26 Ware (2022).

27 Lindegaard (1993): 9.

28 Somerset Record Society (1275) in Lindegaard (1993).

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Richardson (1898).